Iodine and thyroid function: everything you need to know

January is Thyroid Awareness Month, and a great opportunity to discuss iodine and thyroid function. This topic covers one of the most common queries in relation to eating seaweed – how does iodine affect thyroid function? What happens if you eat too much iodine? Is iodine bad for you? In actual fact, it’s thought that hypothyroidism (an underactive thyroid) is more common than hyperthyroidism (an overactive thyroid), and that around 5% of Europe’s population may be suffering from the symptoms caused by a lack of iodine. In this article we will do a deep dive into iodine and thyroid function, as well as the role that seaweed has to play in maintaining a healthy hormone balance.

Table of Contents

What is the thyroid gland?

The thyroid gland (glandula thyreoidea) is a small, butterfly-shaped gland at the base of the neck. It produces the hormones thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). These hormones stimulate and regulate cell metabolism – the speed at which our bodily functions are performed. These include:

- Transformation of food into energy

- Absorption of oxygen

- Breakdown and uptake of glucose

- Breakdown of fats and increase of free fatty acids

- Lowering of cholesterol levels

- Regulation of the rate and strength of the heartbeat

- Fetal and postnatal brain development

- Regulation of sexual functions like libido and menstrual cycles

- Maintenance of regular sleep patterns and focus

Iodine and thyroid function

Iodine is one of the main building blocks of T3 and T4 – the thyroid gland requires it to do its job. Our bodies do not produce iodine naturally, so it’s important that we get enough of it in our diets. Iodine is absorbed into our bloodstream via the bowel, as part of the digestion process. It’s then carried to the thyroid gland, where it is used to create thyroid hormones.

Iodine is found in many food groups, mostly in animal proteins (milk, cheese, eggs, yoghurt, fish, shellfish, beef liver and chicken) but also in seaweed and kelp. This is very important for those following a plant-based diet, especially expectant mothers and young children. Before the iodisation of table salt around 100 years ago, the instances of goiter (a swollen thyroid gland) were concentrated in mountainous, inland regions, which suggests that people living and eating off the coasts and surrounding areas received adequate iodine through their diets:

Prior to the 1920s, endemic iodine deficiency was prevalent in the Great Lakes, Appalachians, and Northwestern regions of the U.S., a geographic area known as the “goiter belt”, where 26%–70% of children had clinically apparent goiter.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3509517/

In the 1920s, a program of salt iodisation began, first in Switzerland and shortly thereafter in the USA:

In 1922, Swiss physician/surgeon Hans Eggenberger campaigned to improve iodine nutrition, petitioning the government to iodize salt, and working with his family to iodize and distribute it in his region. The positive results led to Switzerland’s modern, sustainable salt iodization program today. That in turn led in the 1990s to the creating of the Universal Salt Iodization campaign, a public/private partnership that has led to 89% of the global population having access to iodized salt, protecting the brains of hundreds of millions of children.

https://www.ign.org/how-it-all-began—100-years-of-salt-iodization-in-switzerland.htm

Today, over 120 countries have made iodised salt mandatory to combat iodine deficiency. However, simply increasing your intake of salt is not a sustainable solution to this problem – a high sodium diet carries with it a whole host of other health problems. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health recommends that the average daily intake of salt be no more than 6g, and it’s estimated that many of us eat around 10g of salt each day already. Luckily, we can find both iodine and a natural, salty, umami flavour in seaweed and kelp!

Thyroid dysfunction

An overactive thyroid can lead to hyperthyroidism, whereas an underactive thyroid can lead to hypothyroidism. The American Thyroid Association estimates that up to 30% of the world’s population is at risk of hypothyroidism, mainly due to dietary factors. Let’s take a look at some of the symptoms of these conditions:

Hyperthyroidism symptoms

- nervousness, anxiety and irritability

- hyperactivity – you may find it hard to stay still and have a lot of nervous energy

- mood swings

- difficulty sleeping

- feeling tired all the time

- sensitivity to heat

- muscle weakness

- diarrhoea

- needing to pee more often than usual

- persistent thirst

- itchiness

- loss of interest in sex

Hypothyroidism symptoms

- tiredness

- being sensitive to cold

- weight gain

- constipation

- depression

- slow movements and thoughts

- muscle aches and weakness

- muscle cramps

- dry and scaly skin

- brittle hair and nails

- loss of libido (sex drive)

- pain, numbness and a tingling sensation in the hand and fingers (carpal tunnel syndrome)

- irregular periods or heavy periods

As you can see, there is a considerable amount of overlap in symptoms on the two ends of the spectrum. Symptoms like tiredness, loss of sex drive and muscle weakness are caused by both kinds of thyroid imbalance. Many of these symptoms are easily mistaken for lifestyle-related issues, which can lead to a delay in a proper diagnosis. Another great benefit of having a balanced and nutrient-rich diet is the easy identification of issues that are not diet-related.

Can you have too much iodine?

Hyperthyroidism is most commonly caused by Graves’ disease, an autoimmune condition where the body mistakes the thyroid gland for a foreign body, and attacks it. Around 1 in 20 cases of hyperthyroidism are caused by thyroid nodules – benign lumps that grow on the thyroid and increase its capacity for hormone production beyond what the body needs.

Taking iodine supplements can trigger hyperthyroidism. This is sometimes referred to as the Jod-Basedow phenomenon. However, this usually only happens if you already have thyroid nodules, which account for a minority of hyperthyroidism cases. Most of the time, your body can deal with an excess of iodine in the same way it deals with an excess of any other unwanted nutrient – it simply gets rid of it.

For adults*, the recommended daily intake of iodine is 0.15 milligrams (0.25 milligrams for pregnant and breastfeeding women) with a tolerable upper limit of 1.1 milligrams (meaning that iodine intake up to this level us unlikely to cause adverse health effects). This guideline varies slightly from country to country, so always check your country’s medical advice, or consult with a doctor if you’re unsure.

Seaweed and iodine

Seaweed has been used to treat thyroid-related health problems for nearly 5,000 years. In 2,838 BCE, Emperor Shen Nung – regarded as the father of Chinese medicine and the inventor of acupuncture – wrote prescriptions for seaweed to treat goiter. Its use was noted again in China around a thousand years later, in 1600 BCE, where burnt sea sponge and seaweed were used to treat the disease. Jump forward to 1811, when French chemist Bernard Courtis noticed that the process of burning seaweed to extract potassium nitrate gave off a purple smoke. He identified that active element as iodine by oxidising the burnt seaweed with sulphuric acid. These were the beginnings of the public health successes we’ve seen with iodine today.

However, The American Thyroid Association has estimated that around 30% of the world’s population is at risk of iodine deficiency, and that 5% of Europe’s population has either undiagnosed or diagnosed hypothyroidism. Adding just a pinch of seaweed or seaweed salt to your meal each day is a really great way to maintain a healthy thyroid, and keep your body in balance.

Here’s how much iodine our products contain:

| Product | Iodine content (mg/100g) |

| Arctic Ocean Greens | 49.00 |

| Arctic Seaweed Salt | 4.90 |

| Smoked Seaweed Salt | 11.60 |

| Lofoten Umami | 28.70 |

| Truffle Seaweed Salt | 30.00 |

| Wok & Greens | 28.00 |

| Fish & Seafood | 23.00 |

| BBQ & Meat | 18.00 |

| Seaweed Tagliatelle | 1.14 |

| Algae Pearls | 6.84 |

| Seaweed Bread Mix | 38.00 |

| Winged Kelp | 38.00 |

| Sugar Kelp* (Sweet Kombu) | 170.00 |

| Oarweed* (Kombu) | 420.00 |

| Nori | 2.90 |

| Truffle Seaweed | 200.00 |

| Dulse | 45.00 |

| White chocolate with dulse | 1.13 |

| Dark chocolate with sugar kelp | 6.50 |

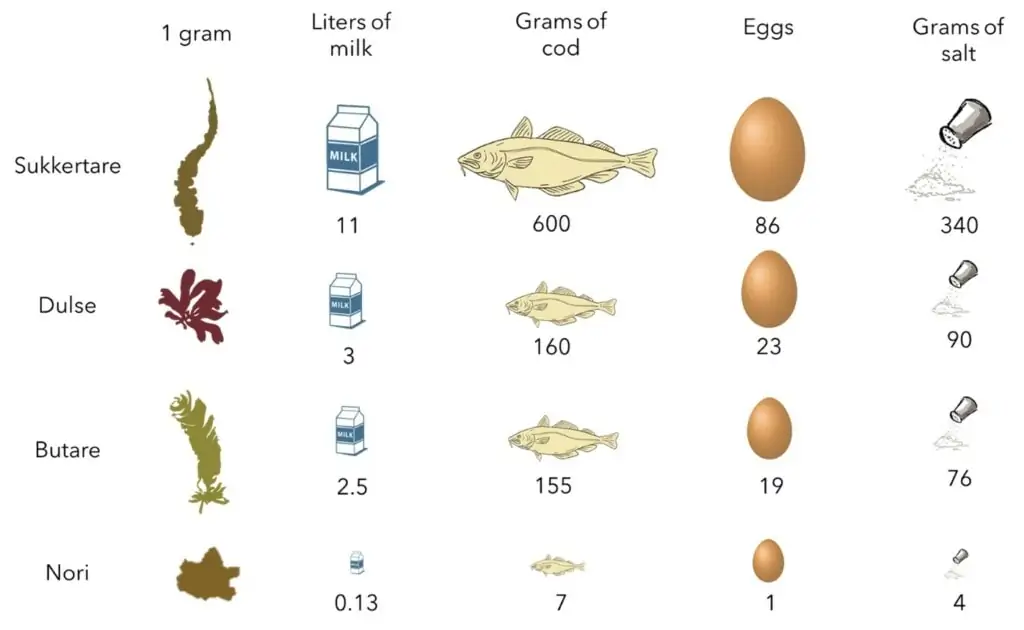

This diagram shows how the iodine contents of milk, fish, eggs and salt stack up to seaweed. As you can see, different types of seaweed have different iodine concentrations. For example, the iodine content of one gram of nori is equivalent to the iodine content of one egg, but you’d need to eat 86 eggs in order to get the same amount of iodine as one gram of sugar kelp!

Our products and recipes are carefully designed with this in mind – we encourage you to use seaweed to unlock the fantastic health benefits of iodine, and to understand that the key to a healthy lifestyle is balance and moderation.

*The iodine content of seaweed is dependent on its species, location, and season in which it was harvested. If you’re currently taking iodine pills or have thyroid problems, consult your doctor before increasing your seaweed intake. Baby food is pre-iodised, so you don’t need to add seaweed to their diets.

*Blanching kelp in hot water for one minute can reduce its iodine content by up to 90% (Nielsen et al., 2020).